Click here to access the presentation Food Sovereignty – From the Ground Up

Click here to access the full Northern Foods Sovereignty Study Report

In 2017-18, Boke facilitated discussions within and between three First Nations communities in northwest Manitoba:

- Barren Lands First Nation in Brochet, on Reindeer Lake

- Northlands Dënesųłiné First Nation, on Lac Brochet

- Sayisi Dene First Nation, on Tadoule Lake

The topic of these discussions was food:

- How can our communities grow more of our own food?

- How can we integrate our traditional food practices—fishing, hunting, gathering, and preserving—with new ways of growing healthy food?

- How can we again take control of our own food sovereignty?

With support from Indigenous Services Canada, Boke’s Curt Hull brought together local food experts from all three communities, along with food experts specializing in new and innovate food growing practices.

They toured the three communities together. They met with elders, youth, and other community members to hear their visions for food in their communities. The Boke team and the local food experts then developed a 5-year plan for food sovereignty in each community.

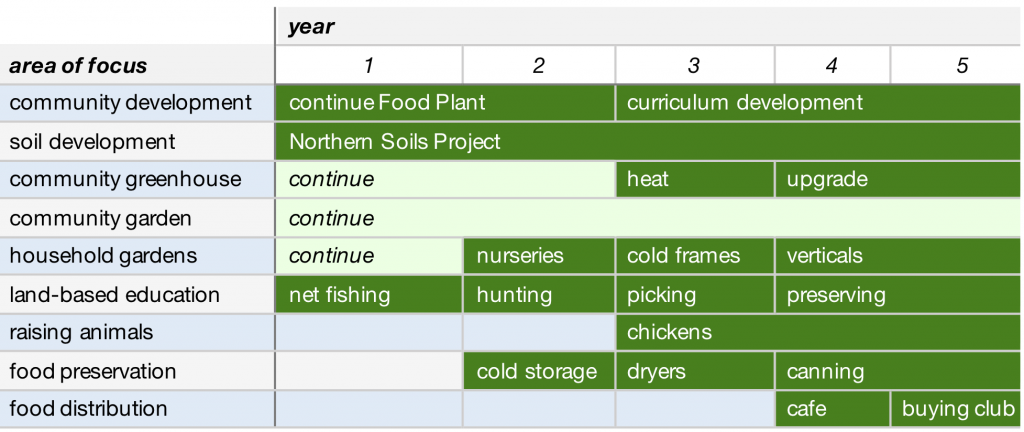

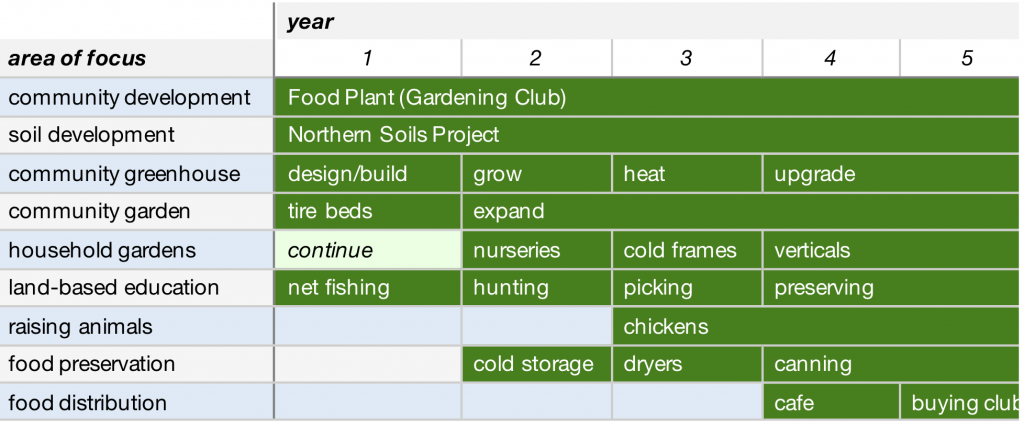

Food Sovereignty Plans

With significant investment from the Government of Canada, and TidesCanada, often with support of the Northern Healthy Foods Initiative and Food Matters Manitoba, and gathered under the umbrella of Northern Manitoba Food, Culture and Community Collaborative (NMFCCC) small and mid-sized gardens and farms—some with associated greenhouses—are starting to appear across Manitoba’s north.

Food Sovereignty Plan Components

Community Development

Food Plant

The Kisipikamak Food Plant (Brochet Food Plant) has been built based on the Ithinto mechisowin: Food from the Land model in South Indian Lake/O-pinon-na-piwin. The goal of the Kisipikamak is to harvest food from the land that can distributed to families in-need and to Elders in the community. As the Food Plant evolves it will be a hub for food initiatives to work collaboratively to increase access to traditional foods and continue passing on food traditions in the community.

People from Northlands Dënesųłiné and Sayisi Dene were very interested in the Food Plant.

Gardening Club

This would be an entity with an organization and support structure to encourage and provide support for people in the community who want to garden. The establishment of a community garden would, in most cases, be an intrinsic component of the Gardening Club initiative. Activities would include support for the community greenhouse and support for people who want to garden on their own

Repurposing Waste

There are a number of types of waste available in communities that can be valuable resources for this project. These include:

- Discarded pop bottles can be cut down to use for seedling and bedding plant planting trays and covers.

- Discarded building components, including wood and nails could be used to make cold frames.

- Wood chips and sawdust left over from harvesting trees for biomass heating, firewood, fencing, and building construction can be used as soil amendments.

- Leftover material from slaughtering animals can be used as soil amendments, once they are properly composted in an in-vessel composter. An in-vessel composter went into Northlands Dënesųłiné as part of a larger recycling and waste initiative. A similar system is needed in Barren Lands and Sayisi Dene.

- Discarded containers, tires and insulated boxes can be used for cold storage and garden beds.

Community and Agency Support

Local health agencies are interested in integrating their healthy foods initiatives with a greenhouse initiative, particularly the Aboriginal Diabetes Initiative that has the mandate to run programs that encourage healthy food and recreation. Other initiatives such as the Brighter Futures Initiative and Jordan’s Principle incorporate gardening and traditional food activities into their programs.

Local schools are interested in integrating their education with growing food. There are well-developed curriculum resources that can provide structure.

There is a network of government and non-government entities that are already established and already interested in these types of initiatives.

The Northern Soils Project

There is little or no existing soil in these communities to grow the kind of plants contemplated. There are, however, components of soil locally available. Those components include:

- sand

- muskeg/peat

- wood chips & sawdust

- scrap paper and cardboard

- material left over from slaughtering animals

- post-consumer organics

A number of things are needed to turn these potential soil components into fertile growing soil.

First, local people will need to be trained and paid to sample, package and ship these potential soil components. Soil experts in the University of Manitoba’s Department of Agriculture will need to be involved to teach local people how to do this work, receive the samples, test them, and provide a “recipe” for turning these components into soil.

They will then need to train local people in creating this soil.

Secondly, we will need some equipment to process the materials. This equipment includes:

- a wood chipper and equipment for acquiring wood.

- a paper and cardboard shredder

- an in-vessel composter, which will combine wood chips, sawdust, scrap paper, cardboard, material left over from slaughtering, and post-consumer organics into finished, commercial-grade compost.

- a bobcat or other heavy equipment for moving bulk composted material, turning rows and adding in feeder stock

Fortunately, for Northlands Dënesųłiné, this equipment is being supplied through two currently-funded projects—the ERAAES (the Environmental Remediation And Alternative Energy Systems) project and a Waste and Recycling project. Similar equipment would need to be purchased for the other communities.

Limitations

The Northern Soils Project is not designed to be commercially viable. The vegetables grown will be consumed by the households that grow them, and by the people they share them with.

Benefits

The Northern Soils Project can set the groundwork needed for commercially-viable food production. In particular, it will develop a way to train people to work in food production.

Perhaps even more importantly, the Northern Soils Project has the potential to change what people eat, and to significantly increase local food production.

It also has the potential to be sustainable. Once the system, building structures and soils are in place, the only cost to continue will be seeds—and some of them can be harvested from the plants being grown.

Just as important, it will divert organic waste from the “dump”.

Community Greenhouses

The greenhouse program proposed here is low cost and sustainable. It is integrated into the education system, health system and the local waste, recycling and energy systems. Most importantly, it builds on work already being done by people living in these communities.

The greenhouse building structures it proposes use almost all local materials. They can be built by local people and are developed organically from the traditional and established local building designs. These structures can cost the same or less than prefabricated greenhouse structures brought in from the south and can last just as long or longer.

Building Community Greenhouses Using Traditional Skills

Community members also have expertise in some of the elements required for northern greenhouses. In particular, there is an expertise in building durable pole-based structures, using a combination of local-sourced materials and plastic sheeting.

A number of features of pole-based design are particularly relevant for greenhouses in northern communities:

- holes are augured into the ground, and the poles are inserted directly into the holes, without a foundation

- the poles are local trees, stripped of bark

- the poles are arranged so that the joints require minimal connectors—usually only a few nails

- in addition to weather protection, the plastic tarpaulin provides structural strength

- they are built entirely with local labour and locally-owned tools

- only the nails and plastic tarpaulin needs to be brought up from the south

- they are derived from local, traditional design

- Inserting the poles into the ground would be a significant problem in the south, where they can be expected to rot in a few years. In these northern communities, because of the density of the local wood, and the lack of organic material in the ground, rotting occurs much more slowly.

This approach has been adapted for the larger summer church located north of the Northlands Denesuline community. This church is approximately 80 feet long, 30 feet wide and 15 feet high at its central peak (25m x 10m x 5m).

Each fall, the plastic tarpaulin is removed, so that the pole structure can survive the winter snow. In spring, any needed repairs are done and the plastic sheeting is put back on.

This pole-based design can be easily adapted to greenhouses. The only design change required would be the use of transparent or translucent sheeting.

Heating

This is the addition of supplementary heat to the greenhouse. The Lac Brochet ERAASE project includes a biomass boiler and district heating loop to provide a locally sustainable source of heat. Once such a system is established in a community, we could consider tying the community greenhouse into the district heating loop. This would lengthen the growing season within the greenhouse.

Upgrading

Upgrading the community greenhouse might take many forms depending upon need and what is practically achievable. It could mean making it larger. It could mean building an additional greenhouse. It could mean adding insulation panels, passive heat systems, cooling fans, temperature sensitive ventilation, and LED grow lights to further extend the usable season of the greenhouse.

Community Garden

The initial establishment of a community garden would be an intrinsic component of the Food Plant or Gardening Club initiative above.

For the summer of 2018, there is funding for two adults and four youth in Barren Lands as gardening advisors. Northern Manitoba Food, Culture, and Community Collaborative (NMFCCC) has been providing this funding since 2014. New sources of funding are necessary for this project to continue in 2019.

Household Gardens

Supporting interested community members in building gardens that serve their household. Raised bed gardens are the most suitable and flexible to add to back yards. The garden bed design has been developed to discourage animal, snow mobile, and human foot traffic to prevent degradation of the soil and protects growing plants. Frames also hold plastic or sheet covers to help with frosts and cold days.

Potato Tire Towers

By creating a tower out of old tires as a way to grow potato plants we are accomplishing a number of things:

- We are creating a new use for otherwise discarded materials. There are many tires in each of these communities that are no longer in use.

- We will have a tried and tested potato growing system. This design will allow each plant to yield a larger crop in a short period of time.

- We are using only a small amount of soil.

Cold Frames

This portion of the project would be to build cold frames for community gardeners.

Once it is warm enough for the plants to survive outside the greenhouse, they would be transferred to cold frames and small greenhouses constructed adjacent to people’s homes.

Families of students most involved in growing seedlings and caring for the plants in the greenhouses would probably be the ones most interested in having a cold frame or greenhouse by their house, but other community members will also be interested.

Local people will need to be recruited and paid to design and construct these cold frames and greenhouses.

Seedling Nurseries

The outdoor growing season is so short in our communities that virtually all food plants need to be started indoors. This requires a heated space and grow lights. Grow lights and trays of seedlings can be setup in very simple vertical racking systems. A nursery project might mean setting up racks in a shared community building. The seedlings would be made available to gardeners when it is time either to plant in outdoor gardens or to transfer to individuals’ greenhouses.

Growing seedlings in classrooms does not have to be expensive or complicated. With the development of LED lighting, it has become even more affordable.

Students could be asked to bring small, discarded drink bottles. These can be cut down to make the containers for the seedlings. This repurposing of used pop bottles is not done, primarily, to save money. Instead, it is one small, specific step that can be taken to link waste and food production.

In discussions we’ve had with community members, the vegetables they express the strongest interest in are onions and potatoes. These are fried up with fish, caribou and moose.

Once the seedlings have sprouted, they can be transferred to “pots” made from larger drink bottles and transferred to a greenhouse near the school.

Until the nights are warm enough for the plants to survive the night, students will need to take the plants out to the greenhouse each morning and bring them back into the school at the end of the day. Because the plants are not intended to grow to maturity in the greenhouse, raised beds and tables are not needed. Lighting isn’t needed and, at least initially, the greenhouses don’t need to be heated.

Land-Based Education

In Canada, “country food” refers to the traditional diets of First Nations, Metis, and Inuit peoples. These foods are fundamentally important to the people in our participating communities, both as sources of nutrition and as central to the cultural life of the communities. The projects proposed are intended to ensure that traditional practices are strengthened and passed on to future generations and to enhance people’s access to these food sources.

Elders/Youth Traditions Transfer

All of the efforts to enhance country food access in these communities include getting elders and youth together so that the youth could learn from the elders. All of the conversations we had in all communities put great importance on educating and engaging youth. Being food secure is important for our future generations. There is a passing on of knowledge in all of these steps.

Net Fishing

After catching the fish, they are cleaned. We will need a fish plant, a community building, where the fish can be cleaned and prepared for storage or consumption. Fish waste is an excellent additive to improving soil quality directly to the garden beds or in the in-vessel composter

Hunting

Community hunting trips happen throughout the year where moose, caribou, geese, and ducks are harvested. Some hunting trips are organized with the local health centre or school to get youth onto the land and learning about their traditional food practices. Any extra meat harvested is also processed and stored in community freezers which can then be used for workshops, feast or Elders and families in need.

Dressing

“Dressing” is all of the processes required to go from a freshly killed animal to something that is ready to preserve or eat, including skinning, eviscerating, and butchering. Buildings or rooms could be dedicated to different processes to ensure food safety and reduce cross contamination.

Berry and Medicine Picking

Local berries are harvested during the warmer months. Berries and medicines are used in a variety of different ways to improve health.

Traditional Preserving

Learning the traditional ways of food preservation is just as important as learning to catch, kill, or pick the food. Once the food has been collected, it is stored until needed. To prolong the storage of the food, it will need to be preserved by either smoking it or drying it in the sun.

Raising Animals

Members of all three communities expressed interest in having a chicken coop and system for raising chickens along the lines of the Meechim Project in Garden Hill First Nation.

Food Preservation

Cold Storage

This could be a simple as a chest freezer for community use, such as currently exists in Barren Lands / Brochet. It could also be a larger community food locker where community members have secure access to locked boxes within a shared container.

There is potential to build cold storage rooms, and cellars. These can be buried and created out of insulated boxes, including old freezers and fridges for households. Cold storage is essential for maintaining the quality of root crops throughout the winter.

Drying Vegetables

This involves building dehydrators. It might be possible to use heat from a sustainable biomass, district heating system for this. It is also possible to augment that heat source with some solar. Solar dehydrators are used at the Northern Sun Farm Co-op south of Steinbach.

Canning

Canning is a process that will allow for the preservation of many types of food. This will include fish, fruits and vegetables. If this process becomes popular, shelving will need to be added to the storage lockers.

Food Distribution

Café

Starting up a café or restaurant within the community is possible. This would be as much a place for informal social interaction as it would be a place for accessing food. It could include a local grocery.

Buying Club

Groups of people or families can come together to purchase bulk quantities of food. This is a system that can be set up and run out of the cafe for the community. The food would be more cost efficient and bring less waste and packaging into the community.

Social Media

We should use social media such as Facebook to increase the reach of whatever mechanisms we use or distribution of healthy, affordable food. This form of communication has really become popular and is widely used as remote communities get more Wi-Fi and internet connection.